An Unexpected Aphid in Strawberries

go.ncsu.edu/readext?250847

en Español / em Português

El inglés es el idioma de control de esta página. En la medida en que haya algún conflicto entre la traducción al inglés y la traducción, el inglés prevalece.

Al hacer clic en el enlace de traducción se activa un servicio de traducción gratuito para convertir la página al español. Al igual que con cualquier traducción por Internet, la conversión no es sensible al contexto y puede que no traduzca el texto en su significado original. NC State Extension no garantiza la exactitud del texto traducido. Por favor, tenga en cuenta que algunas aplicaciones y/o servicios pueden no funcionar como se espera cuando se traducen.

Português

Inglês é o idioma de controle desta página. Na medida que haja algum conflito entre o texto original em Inglês e a tradução, o Inglês prevalece.

Ao clicar no link de tradução, um serviço gratuito de tradução será ativado para converter a página para o Português. Como em qualquer tradução pela internet, a conversão não é sensivel ao contexto e pode não ocorrer a tradução para o significado orginal. O serviço de Extensão da Carolina do Norte (NC State Extension) não garante a exatidão do texto traduzido. Por favor, observe que algumas funções ou serviços podem não funcionar como esperado após a tradução.

English

English is the controlling language of this page. To the extent there is any conflict between the English text and the translation, English controls.

Clicking on the translation link activates a free translation service to convert the page to Spanish. As with any Internet translation, the conversion is not context-sensitive and may not translate the text to its original meaning. NC State Extension does not guarantee the accuracy of the translated text. Please note that some applications and/or services may not function as expected when translated.

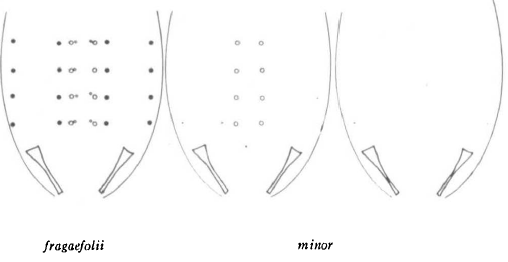

Collapse ▲Last week, I examined a patch of strawberries in a garden just outside our lab in Raleigh, NC. I was hoping to find some strawberry aphids (Chaetosiphon fragaefolii) to photograph as part of a project on aphid vector of viruses in strawberries. After a very short search, I was amazed at my luck when I found some aphids with the clubbed hairs that distinguish strawberry aphids from other species that feed on strawberries. However, something was not quit right about these aphids. Instead of having clubbed hairs all over their bodies, they only had them on their heads and the last few segments of their abdomens. With help from Dr. Matt Bertone at the NCSU Plant Disease and Insect Clinic, the mysterious aphids’ identity was revealed to be the closely related Chaetosiphon minor.

Chaetosiphon minor collected on strawberries in Raleigh, NC. The white arrows point toward the clubbed hairs on the head and abdomen. Photo: Matt Bertone.

An occasional pest of strawberries, Chaetosiphon minor is not a new aphid to the area, or even the country. It has been documented in most of the eastern U.S. and southern Canada since the early 1900’s. It rarely reaches economically damaging levels of infestation, and as a result little has been researched about its natural history. Similar to the strawberry aphid, C. minor feeds on the underside of foliage close to the leaf veins. Like most aphids, it has a non-winged form that reproduces parthenogenetically and more mobile winged forms that reproduce sexually. It is reported to overwinter in the egg stage, at least in northern states.

C. minor has been shown to vector strawberry yellow edge virus, but other Chaetosiphon species, such as the strawberry aphid, are better documented virus vectors. The fact that we have found virus vectors in addition to C. fragaefolii suggests that we may need to take a closer look at aphid diversity in North Carolina strawberries.

Differences in hairs on the abdomens of the strawberry aphid (C. fragaefolii) and C. minor. Notice that some C. minor have a row of simple hairs down the abdomen and some have none. Image via G. A. Schafers (1960)

See more information about other strawberry infesting aphids and aphid management.

More information

What to watch for: Aphids in strawberries – NC Small Fruit & Specialty Crop IPM