Spotted-Wing Drosophila Needs Assessment, 2011

go.ncsu.edu/readext?625301

en Español / em Português

El inglés es el idioma de control de esta página. En la medida en que haya algún conflicto entre la traducción al inglés y la traducción, el inglés prevalece.

Al hacer clic en el enlace de traducción se activa un servicio de traducción gratuito para convertir la página al español. Al igual que con cualquier traducción por Internet, la conversión no es sensible al contexto y puede que no traduzca el texto en su significado original. NC State Extension no garantiza la exactitud del texto traducido. Por favor, tenga en cuenta que algunas aplicaciones y/o servicios pueden no funcionar como se espera cuando se traducen.

Português

Inglês é o idioma de controle desta página. Na medida que haja algum conflito entre o texto original em Inglês e a tradução, o Inglês prevalece.

Ao clicar no link de tradução, um serviço gratuito de tradução será ativado para converter a página para o Português. Como em qualquer tradução pela internet, a conversão não é sensivel ao contexto e pode não ocorrer a tradução para o significado orginal. O serviço de Extensão da Carolina do Norte (NC State Extension) não garante a exatidão do texto traduzido. Por favor, observe que algumas funções ou serviços podem não funcionar como esperado após a tradução.

English

English is the controlling language of this page. To the extent there is any conflict between the English text and the translation, English controls.

Clicking on the translation link activates a free translation service to convert the page to Spanish. As with any Internet translation, the conversion is not context-sensitive and may not translate the text to its original meaning. NC State Extension does not guarantee the accuracy of the translated text. Please note that some applications and/or services may not function as expected when translated.

Collapse ▲As it became clear in 2011 that spotted wing drosophila (SWD) had become a significant pest of fruit in the eastern US, a group of entomologists at Cornell, Rutgers, Michigan State, and NC State Universities (now participants in the eFly Working Group) conducted an online stakeholder needs assessment. The goal of this survey was to focus our research, extension, and education programs in order to best meet stakeholder needs.

We distributed links to the survey via email to county extension agents, grower associations, and regional listserves. A link to the survey was also posted on the NC Small Fruit & Specialty Crop IPM blog. All questions were voluntary, and responses were anonymous. The survey was available from 1 November through 1 December 2011.

What did we ask?

We collected minimal demographic information (age, sex, state of residence, size of farm, and profession) to help us in interpreting responses. We also asked what small fruit crops were grown on respondents’ farms and how they preferred to receive education and outreach information.

Next, we asked respondents to rank 40 possible research and extension activities on a 1 to 10 scale, with 1 least important and 10 most important. We then averaged rankings by the number of responses and compared rankings across farm size and profession.

Who responded to the survey?

We received 273 responses to our online survey and 45 participants in NJ. Responses were evenly distributed throughout the eastern US, the Southeast (82), Midwest (88), and Northeast (89); 14 respondents either declined to provide their state of residence or lived outside of the eastern US. Fifty five of the online respondents were female, while 216 were male, and two declined to provide their gender.

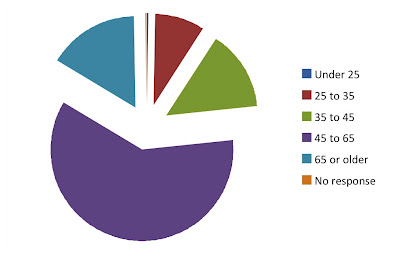

Only one respondent was less than 25, while the largest number of responses were from those 45 to 65 years old.

Age distribution of stakeholders responding to 2011 SWD needs assessment survey. Figure: Hannah Burrack

We specifically targeted blueberry and caneberry (blackberry and raspberry) growers, the crops which had experienced the most SWD damage in the eastern US, but respondents also grew a wide range of other crops including: apples, cherries, currents, elderberry, figs, grapes, gooseberries, peaches, persimmons, pears, plums, and strawberries.

What SWD research and extension activities did respondents consider most and least important?

We calculated rankings for research and extension activities for all respondents and for subsets of respondents based on farm size and profession.

All responses

When we grouped all the responses together, the top and bottom five activities were:

Top Five Activities

1. Insecticide efficacy against SWD (rating: 8.94)

2. Insecticide residual activity against SWD (8.91)

3. Insecticide residues & time from harvest to meet maximum residue levels (MRLs) (8.75)

4. Online management guides (8.74)

5. Identification of native natural enemies (8.64)

Bottom Five Activities

36. Association with wild hosts (6.90)

37. Sprayer performance comparisons (6.81)

38. Insecticide implications for export markets (5.43)

39. Off line (hard copy) trap capture reports (5.12)

40. Management in tunnel systems (4.77)

Small sized growers

We received 80 responses from fruit farms smaller than 10 acres, and when these were grouped together, the highest and lowest ranked responses were:

Top Five Activities

1. Online management guides (8.90)

2. Identification of native natural enemies (8.87)

3. Insecticide residues & time from harvest to meet maximum residue levels (MRLs) (8.84)

4. Insecticide effects on natural enemies and/or pollinators (8.47)

5. Insecticide efficacy against SWD (8.70)

Bottom Five Activities

36. Association with wild hosts (7.04)

37. Sprayer performance comparisons (6.86)

38. Off line (hard copy) trap capture reports (5.20)

39. Management in tunnel systems (4.04)

40. Insecticide implications for export markets (4.01)

Medium sized growers

We received 55 responses from fruit farms ranging from 10 to 50 acres, and when these were grouped together, the highest and lowest ranked responses were:

Top Five Activities

1. Insecticide residual activity against SWD (9.07)

2. Insecticide efficacy against SWD (9.04)

3. Insecticide residues & time from harvest to meet maximum residue levels (MRLs) (8.87)

4. Management in open fields (8.80)

5. Online management guides (8.53)

Bottom Five Activities

36. Effects of irrigation & water management on SWD (6.37)

37. Association with wild hosts (6.32)

38. Insecticide implications for export markets (5.02)

39. Off line (hard copy) trap capture reports (4.42)

40. Management in tunnel systems (4.14)

Large sized growers

We received 27 responses from fruit farms ranging from 50 to 100 acres, and when these were grouped together, the highest and lowest ranked responses were:

Top Five Activities

1. Insecticide efficacy against SWD (9.43)

2. Insecticide residual activity against SWD (9.31)

3. Insecticide residues & time from harvest to meet maximum residue levels (MRLs) (9.15)

4. Insecticide effects on natural enemies and/pollinators (9.12)

5. Integration with current integrated pest management and/or brown marmorated stink bug (BMSB) management (9.08)

Bottom Five Activities

36. Effects of irrigation & water management on SWD (6.77)

37. Insecticide implications for export markets (6.67)

38. Association with wild hosts (6.35)

39. Off line (hard copy) trap capture reports (5.71)

40. Management in tunnel systems (4.00)

Very large sized growers

We received 34 responses from fruit farms larger than 100 acres, and when these were grouped together, the highest and lowest ranked responses were:

Top Five Activities

1. Insecticide residual activity against SWD (9.44)

2. Insecticide efficacy against SWD (9.41)

3. Insecticide residues & time from harvest to meet maximum residue levels (MRLs) (8.94)

4. Identification of native natural enemies (8.77)

5. Insecticide effects on natural enemies and/or pollinators (8.71)

Bottom Five Activities

36. Sprayer performance comparisons (6.76)

37. Insecticide implications for export markets (6.71)

38. Effects of irrigation & water management on SWD (6.59)

39. Off line (hard copy) trap capture reports (5.26)

40. Management in tunnel systems (3.94)

Agricultural professionals

We received 59 responses from cooperative extension agents, crop consultants, regulators, university researchers, and graduate students. When these were grouped together, the highest and lowest ranked responses were:

Top Five Activities

1. Insecticide efficacy against SWD (9.27)

2. Insecticide residual activity against SWD (9.21)

3. Management in open fields (9.07)

4. Online management guides (8.72)

5. Host preference (8.57)

Bottom Five Activities

36. Sprayer performance comparisons (6.96)

37. Effects of irrigation & water management on SWD (6.95)

38. Management in tunnel systems (6.67)

39. Insecticide implications for export markets (6.04)

40. Off line (hard copy) trap capture reports (5.36)

General public

Finally, we received 16 responses from master gardeners, homeowners, and other members of the general public. When these were grouped together, the highest and lowest ranked responses were:

Top Five Activities

1. Insecticide effects on natural enemies and/or pollinators (9.50)

2. Biological control (9.27)

3. Identification of native natural enemies (9.13)

4. Cultural/non chemical management tools (9.00)

5. Integration with current integrated pest management (IPM) and/or brown marmorated stink bug (BMSB) management (8.71)

Bottom Five Activities

36. Degree-day models (6.20)

37. Management in tunnel systems (6.15)

38. Sprayer performance comparisons (6.14)

39. Novel pesticide strategies such as chemigation, pesticide combinations, and/or synergists (5.46)

40. Off line (hard copy) trap capture reports (4.67)

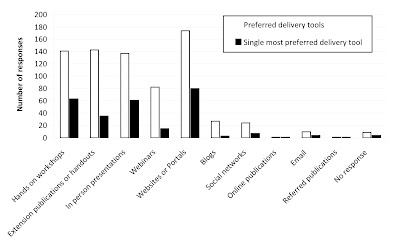

How did respondents want to receive research and educational information?

Perhaps not surprisingly, respondents to the online survey preferred online information delivery tools. However, this presumably web savvy audience also exhibited a strong preference for hands on workshops, in person presentations, and extension publications very highly, suggesting that duel delivery modes for extension and education information would be desirable.

Preferred information delivery mechanisms for respondents to 2011 online SWD needs assessment. Figure: Hannah Burrack

The information generated by this survey was used to craft research projects, grant proposals to fund these projects, and to information extension and education efforts. This survey was an important precursor to the development of the eFly SWD Working Group.