Strawberry Pollination Basics

go.ncsu.edu/readext?422675

en Español / em Português

El inglés es el idioma de control de esta página. En la medida en que haya algún conflicto entre la traducción al inglés y la traducción, el inglés prevalece.

Al hacer clic en el enlace de traducción se activa un servicio de traducción gratuito para convertir la página al español. Al igual que con cualquier traducción por Internet, la conversión no es sensible al contexto y puede que no traduzca el texto en su significado original. NC State Extension no garantiza la exactitud del texto traducido. Por favor, tenga en cuenta que algunas aplicaciones y/o servicios pueden no funcionar como se espera cuando se traducen.

Português

Inglês é o idioma de controle desta página. Na medida que haja algum conflito entre o texto original em Inglês e a tradução, o Inglês prevalece.

Ao clicar no link de tradução, um serviço gratuito de tradução será ativado para converter a página para o Português. Como em qualquer tradução pela internet, a conversão não é sensivel ao contexto e pode não ocorrer a tradução para o significado orginal. O serviço de Extensão da Carolina do Norte (NC State Extension) não garante a exatidão do texto traduzido. Por favor, observe que algumas funções ou serviços podem não funcionar como esperado após a tradução.

English

English is the controlling language of this page. To the extent there is any conflict between the English text and the translation, English controls.

Clicking on the translation link activates a free translation service to convert the page to Spanish. As with any Internet translation, the conversion is not context-sensitive and may not translate the text to its original meaning. NC State Extension does not guarantee the accuracy of the translated text. Please note that some applications and/or services may not function as expected when translated.

Collapse ▲Strawberry flower morphology and seed set

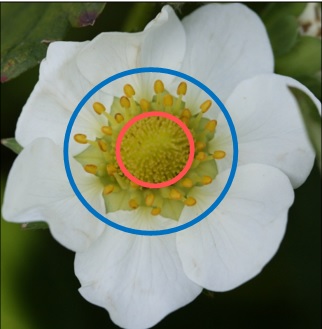

Strawberry flowers have both male and female parts on each bloom. The male parts include the pollen carrying portion of the flower (highlighted in blue) and pollinators must come into contact with this area to collect pollen grains. The female parts of the flower (highlighted in pink) must individually receive pollen grains to attain complete pollination.

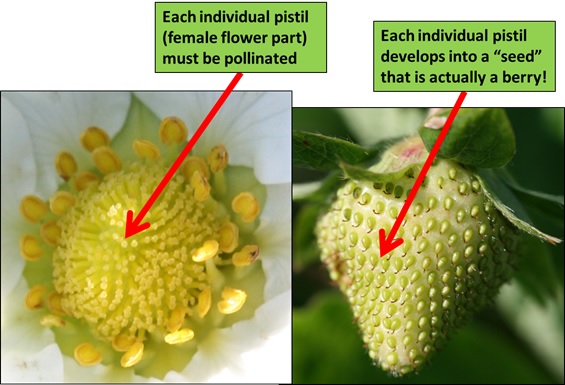

Lack of complete pollination in each pistil (female flower part) can result in smaller or misshapen berries, meaning reduced yield of marketable fruit.

The actual berry forms from each pistil developing into an individual “seed’ that is actually an individual fruit, called an achene. The fleshy red part of the strawberry is rather an enlarged receptacle that holds the achenes (Poling, 2012).

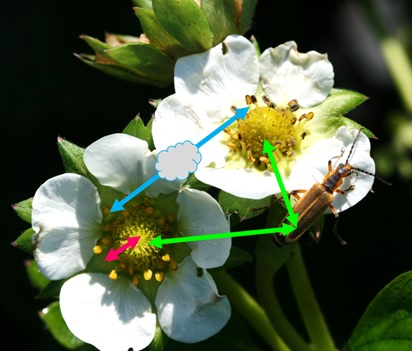

As seen in the photo below, there are many ways for pollen to be transferred within the flower and unlike some crops, strawberries are self-fertile. However, maximum yields are possible with a combination of self-pollination (pink), wind (blue), and insects (green).Although flowers are capable of self-pollinating, each pistil must receive pollination, and studies have shown that self-pollination and wind-blown pollen are often not sufficient to completely pollinate a flower. Only about 60-70% of maximum pollination results from these vectors alone, and open pollination with the aid of insects is necessary for the greatest yield. Insect pollination can also improve strawberry quality and shape, meaning that berries last longer and look fuller!

References:

- Klatt, B. K., Holzschuh, A., Westphal, C., Clough, Y., Smit, I., Pawelzik, E., & Tscharntke, T. (2014). Bee pollination improves crop quality, shelf life and commercial value. R. Soc. B, 281.

- Wietzke, A., Westphal, C., Kraft, M., Gras, P., Tscharntke, T., Pawelzik, E., & Smit, I. (2016). Pollination as a key factor for strawberry fruit physiology and quality. Berichte Aus Dem Julius Kühn-Institut, 183, 49–50.

- Zebrowska, J. (1998). Influence of pollination modes on yield components in strawberry (Fragaria x ananassa Duch.). Plant Breeding, 117(3), 255–260.

(Written by Jeremy Slone, August 2016)