Brown Marmorated Stink Bug in North Carolina

go.ncsu.edu/readext?1053531

en Español / em Português

El inglés es el idioma de control de esta página. En la medida en que haya algún conflicto entre la traducción al inglés y la traducción, el inglés prevalece.

Al hacer clic en el enlace de traducción se activa un servicio de traducción gratuito para convertir la página al español. Al igual que con cualquier traducción por Internet, la conversión no es sensible al contexto y puede que no traduzca el texto en su significado original. NC State Extension no garantiza la exactitud del texto traducido. Por favor, tenga en cuenta que algunas aplicaciones y/o servicios pueden no funcionar como se espera cuando se traducen.

Português

Inglês é o idioma de controle desta página. Na medida que haja algum conflito entre o texto original em Inglês e a tradução, o Inglês prevalece.

Ao clicar no link de tradução, um serviço gratuito de tradução será ativado para converter a página para o Português. Como em qualquer tradução pela internet, a conversão não é sensivel ao contexto e pode não ocorrer a tradução para o significado orginal. O serviço de Extensão da Carolina do Norte (NC State Extension) não garante a exatidão do texto traduzido. Por favor, observe que algumas funções ou serviços podem não funcionar como esperado após a tradução.

English

English is the controlling language of this page. To the extent there is any conflict between the English text and the translation, English controls.

Clicking on the translation link activates a free translation service to convert the page to Spanish. As with any Internet translation, the conversion is not context-sensitive and may not translate the text to its original meaning. NC State Extension does not guarantee the accuracy of the translated text. Please note that some applications and/or services may not function as expected when translated.

Collapse ▲ The brown marmorated stink bug (BMSB, Halyomorpha halys) was accidentally introduced from Asia to North America in the 1990s, with the first detection occurring in Allentown, Pennsylvania, in September 1998. Its first appearance in North Carolina was in Forsyth County in 2009, and it then spread rapidly throughout the piedmont and mountain regions of the state. It has not become as prevalent in the coastal plain, although there have been isolated occurrences. As of February 2025, BMSB had been confirmed in 80 of NC’s 100 counties (and in 47 US states).

The brown marmorated stink bug (BMSB, Halyomorpha halys) was accidentally introduced from Asia to North America in the 1990s, with the first detection occurring in Allentown, Pennsylvania, in September 1998. Its first appearance in North Carolina was in Forsyth County in 2009, and it then spread rapidly throughout the piedmont and mountain regions of the state. It has not become as prevalent in the coastal plain, although there have been isolated occurrences. As of February 2025, BMSB had been confirmed in 80 of NC’s 100 counties (and in 47 US states).

BMSB in North Carolina Fact Sheet

There are many other species of stink bug in North Carolina, including the common brown stink bug (Euschistus servus) and green stink bug (Chinavia hilaris). Most of these species are native to the Southeast and have many natural enemies that keep their populations in check. Historically, they have caused some damage to crops but can usually be managed easily, and they do not overwinter in structures. Some species actually prey on other insects and are beneficial to humans.

In contrast, BMSB has few native natural enemies in North America, making it a highly destructive pest on a wide variety of crops, and an incredible nuisance when it invades homes and other buildings in the fall. It usually establishes first in urban landscapes, roadside vegetation, and structures that provide attractive overwintering sites. This was the case in North Carolina, where most early reports came from property owners between Raleigh and Asheville (the I-40 corridor) who experienced BMSB “invasions” in late summer. Sightings in home gardens and on commercial farms increased from extremely isolated instances in 2010 to widespread problems by 2015. In some cases, populations became large enough that emergency pesticide applications were necessary to prevent extensive crop loss. By 2025, BMSB had become a regular pest on most farms, but ongoing research has helped growers adopt routine monitoring and pesticide programs to minimize crop damage.

(Our research focuses primarily on controlling BMSB in agriculture. For information on dealing with BMSB around the house, visit our FAQ page.)

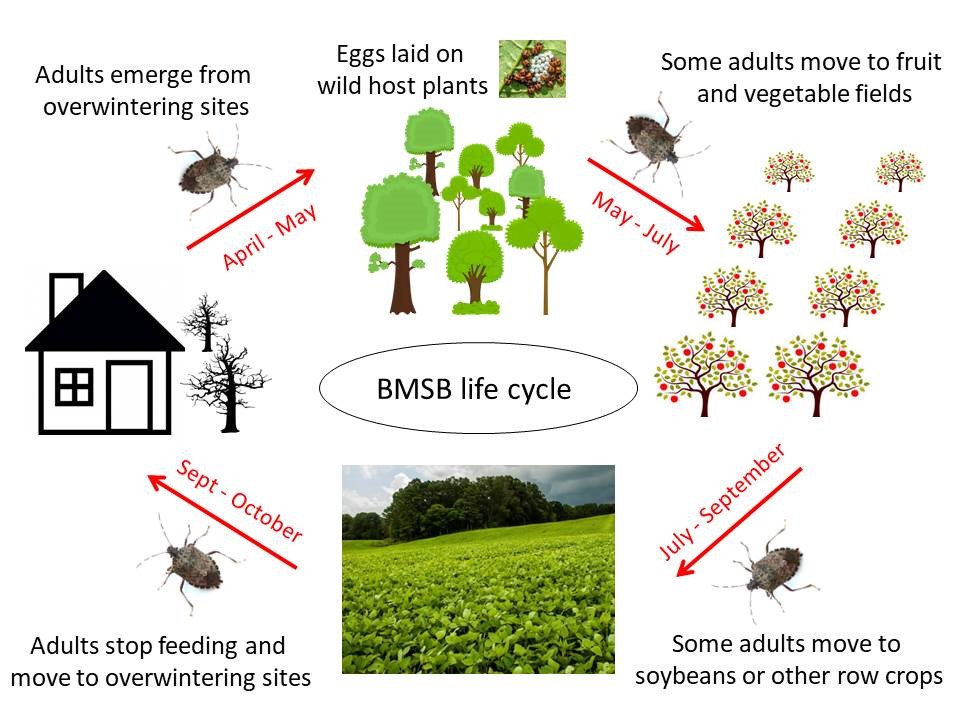

Life cycle in North Carolina

In September and October, brown marmorated stink bug adults move into structures, dead trees, and other sheltered places to overwinter. They may move around on warm days, but generally they remain in diapause, a hibernation-like state of reduced activity. While overwintering they do not feed or lay eggs. Except for their annoying presence, they do not harm people or pets. They usually do not damage property, although in large numbers they have been known to clog heat pumps and power equipment.

In spring, overwintered adults leave their shelters and are seldom found indoors again until late summer. They move onto nearby trees and shrubs where they mate and lay eggs on suitable host plants. By midsummer, the eggs hatch and the nymphs pass through five stages (“instars”) before becoming adults. Many of these 1st-generation BMSB invade farms and gardens as fruit and vegetables mature. Later in the season they may move into soybeans and other field crops. When conditions are ideal (i.e., long periods of warm temperatures with favorable hosts present), a second generation of adults may be produced.

In spring, overwintered adults leave their shelters and are seldom found indoors again until late summer. They move onto nearby trees and shrubs where they mate and lay eggs on suitable host plants. By midsummer, the eggs hatch and the nymphs pass through five stages (“instars”) before becoming adults. Many of these 1st-generation BMSB invade farms and gardens as fruit and vegetables mature. Later in the season they may move into soybeans and other field crops. When conditions are ideal (i.e., long periods of warm temperatures with favorable hosts present), a second generation of adults may be produced.

When days become shorter in early August, adult BMSB stop laying eggs. In September and early October, they begin looking for overwintering sites, and by late autumn, most individuals have settled back into buildings and other sheltered places. The months of September and October, when adults are aggregating in large numbers, are usually when new invasions are observed.

What’s being done?

Beginning in 2011, NCSU entomologists were part of a collaboration of over 50 scientists working on the biology and management of BMSB in the United States. Initially we helped introduce emergency pesticide programs to minimize crop damage, which had totaled $37 million in the 2010 mid-Atlantic apple harvest alone. Broad-spectrum pyrethroids and neonicotinoids proved to be the most effective chemicals for managing BMSB, but their extensive use is not sustainable. They have increased production costs and disrupted IPM programs, resulting in secondary pest outbreaks and greater risk to non-target organisms. Some crops, such as ‘Granny Smith’ apples, continue to be heavily damaged by BMSB despite the use of aggressive insecticide programs.

Therefore, in recent years the focus of BMSB research has shifted toward finding management strategies that will be effective and safe over the long term. In recent years, our collaborative network has developed convenient monitoring traps and attractants, which have helped gauge the severity of local BMSB populations and establish preliminary spray thresholds, reducing the frequency of insecticide applications. We have gained a clearer understanding of the BMSB life cycle in North America, and identified many of the wild plants (several of which are invasive exotics) that BMSB favor to complete their development. We have tested non-insecticidal management tools, such as trap crops, attract-and-kill stations, and protective netting – approaches which may not be practical on many farms, but have shown promise in small or specialized operations.

Therefore, in recent years the focus of BMSB research has shifted toward finding management strategies that will be effective and safe over the long term. In recent years, our collaborative network has developed convenient monitoring traps and attractants, which have helped gauge the severity of local BMSB populations and establish preliminary spray thresholds, reducing the frequency of insecticide applications. We have gained a clearer understanding of the BMSB life cycle in North America, and identified many of the wild plants (several of which are invasive exotics) that BMSB favor to complete their development. We have tested non-insecticidal management tools, such as trap crops, attract-and-kill stations, and protective netting – approaches which may not be practical on many farms, but have shown promise in small or specialized operations.

We have also evaluated the effectiveness of native and non-native predators and parasitoids of BMSB. The most promising of these, Trissolcus japonicus, is a native of Asia that has entered North America with BMSB, and it has the potential to reduce BMSB populations at the landscape level. In coming years, we will participate in a multi-state collaborative project quantifying the effectiveness of T. japonicus in parasitizing BMSB egg masses in apple and peach orchards, with the hopes of eventually augmenting T. japonicus populations in North Carolina.

We have also evaluated the effectiveness of native and non-native predators and parasitoids of BMSB. The most promising of these, Trissolcus japonicus, is a native of Asia that has entered North America with BMSB, and it has the potential to reduce BMSB populations at the landscape level. In coming years, we will participate in a multi-state collaborative project quantifying the effectiveness of T. japonicus in parasitizing BMSB egg masses in apple and peach orchards, with the hopes of eventually augmenting T. japonicus populations in North Carolina.

Report your experiences

- Since 2011, NC State University has been collecting information about BMSB occurrences through an online survey. If you live in NC and have seen BMSB in an area not currently represented on our map, please complete our short survey.

Frequently asked questions

Click the FAQ page for the most common concerns.